Loussac, Z. J. “Zach”

1882-1965 | Druggist, Philanthropist, and Mayor of Anchorage (1948-1951)

To twenty-first century Anchorageites, the name Loussac will more likely ring a bell as the name of the city’s public library, “the Loussac.” To mid twentieth century residents, Z. J. Loussac (or “Zach,” as he became known to virtually everyone) was a pharmacist, civic leader, landowner, and philanthropist who gave back most of his fortune to the community. He was Anchorage’s greatest benefactor and left a legacy of fortune and good will to the city.1 Evangeline Atwood, in Anchorage: All-American City (1957) said: “Loussac’s memory will live in the hearts of future generations, not because of the private fortune he amassed but because of what he did with that fortune. The youth of Anchorage will enjoy untold opportunities through the Loussac Foundation. He was the first Alaskan to share his wealth with his hometown. Others have taken their wealth to the states, when they retired from business.”2

Early Years

Zadrich Joshua Loussac (also known as Zachary and “Zach”) was born on July 13, 1882 to Jewish parents, Vladimir and Rosalie Loussac, in Pokrov, Russia, located about thirty miles from Moscow. Loussac’s father owned a small shop or factory that made picture frame moldings.3

In 1899, Loussac graduated from the Real Gymnasium (the equivalent of an American high school) in Moscow.4 Loussac then entered the prestigious Imperial Polytechnical Institute in Moscow to study engineering. He was expelled during his first year after being accused of “participating in a revolutionary movement.”5 He explained that this charge was based on the fact that he had come under scrutiny for “studying some of the more liberal literature of the time.” He had read the works of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and pamphlets published by socialists and anarchists. He went to southern Russia to visit his grandmother, and then crossed the border to Germany after learning that government officials were searching for him.

In 1900, Loussac arrived in New York City at the age of eighteen, nearly broke and unable to speak English. He managed to get himself a job running errands for a drug store in a Russian neighborhood on the lower East Side. While working in the drug store, he heard glowing tales of the discovery of gold from a man returning from the Klondike, which he thought was in Alaska, and became infected with gold fever.6

Finding Alaska

In 1901, Loussac set off for Alaska and got as far as Great Falls, Montana, before running out of money. Luckily, the clerk for the only drug store in town had just been fired and he was hired to replace him. Six months’ work was enough to raise money to return to New York. He attended the New York College of Pharmacy which later became part of Columbia University. In 1903, Loussac graduated and was hired as pharmacist in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel drug store.7

However, his dreams of going to Alaska to strike it rich were as bright as ever. Several years later, in 1907, two visiting U.S. senators, William Stuart of Nevada and Samuel Piles of Washington, wearing big western hats entered the pharmacy and told him all about the wild west. They were so enthusiastic about the west that he got the same spirit. They encouraged him to follow his Alaskan dream. He said: “That was enough for me. I quit my job, took my pharmacist license off the wall, peeled some bills off my $450 bankroll and bought a ticket to Seattle.”8

Loussac’s railroad trip west to Seattle ran into trouble after his arrival. He had to wait three months for a steamboat to Alaska and during the stay, depleted his savings. He boarded a Canadian ship, Transit, at Vancouver with passage to Nome. The voyage lasted forty-two days, including two weeks of which the ship was icebound in the Bering Sea.

Nome

Loussac arrived in Nome on July 12, 1907. From Nome, at age twenty-five, he entered into an unsuccessful partnership to lease a mining claim near New Solomon on the Seward Peninsula. Loussac and his two partners promptly went broke. They ended up walking forty miles back to Nome, where Loussac sold his fur coat and gold collar studs to buy a ticket back to Seattle. He worked as a pharmacist in the cities of Seattle and San Francisco until the summer of 1908.9

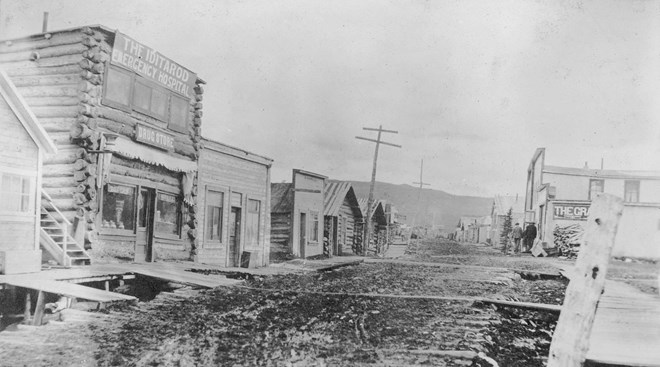

Haines and Iditarod

In 1908 Loussac took a position as a manager of a drug store in Haines, Alaska. In 1909, he learned of the Iditarod gold strike. Loussac left Haines in 1910, and he and a partner, Jimmy Fay, opened a tent drug store in the booming mining community of Iditarod. The merchant in the next tent was Isadore (“Ike”) Bayles, who was to become a long-time friend and fellow businessman in Anchorage. In April 1911, a great fire leveled the entire Iditarod business block, including Loussac’s drug store. He built a magnificent two-story building and borrowed $20,000 from bankers to start the new store but had timed his new venture poorly. In spring 1911, miners began leaving Iditarod for a new gold strike at Ruby. When they did not return, the remaining businesses went bankrupt. His business was taken over by several banks, and he was left with a debt between $4,000 and $5,000.10 Loussac went back to San Francisco, where he was hired by the Owl Drug Company.

Juneau

While in San Francisco, Loussac joined a club of Alaskans which was supporting newspaperman John Strong for territorial governor. President Woodrow Wilson appointed Strong as governor in 1913. After taking office, Strong invited Loussac to come to Juneau “when a drug store needed a man.”11 Loussac took up residence in Juneau in the spring of 1913 and opened the Juneau Drug Company on 107 Front Street, across from the Alaskan Hotel.12

Anchorage (1916-1953)

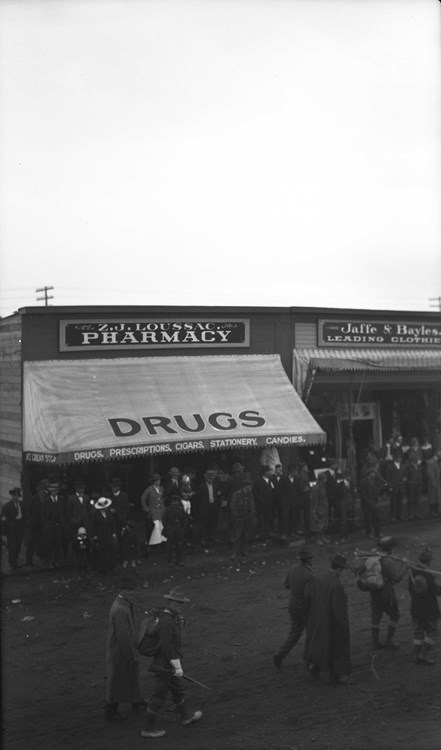

In 1915, Loussac’s attention was drawn to Knik Arm, the site of the construction headquarters for the Alaska Railroad. In 1916, he traveled to Anchorage. “I came and looked around. I came across my old neighbor at Iditarod, Mr. Bayles. He was thinking of putting in a men’s store just like the one he had at Iditarod. We went together and bought a lot at Fourth Avenue and D Street. He built his men’s store and I built my drug store next door, just like Iditarod. We each had buildings about 25 by 50 feet. My Anchorage store grew fast and I found I couldn’t be in two places at once so I sold my Juneau store and moved to Anchorage to live. This was June 1916. There was still a tent city on the Ship Creek flats, but the business establishments on Fourth Avenue were taking shape.”13

Loussac opened his first Anchorage drug store at 403 Fourth Avenue, then the commercial and business center of the town. He adopted the slogan “We’ve got what you want when you want it.” According to Evangeline Atwood, Loussac “gained a reputation for being a wide-awake, progressive merchant.”14 He continually offered special services to his customers. For example, in the early days when business was not as brisk as it became during World War II, he set up a desk with free paper and envelopes for anyone wishing to write a letter. He had a free delivery service. There was a mail service which guaranteed that orders were sent out the same day they were received. He invited customers to play the latest phonograph records and had a large stack of records listeners could use.15 There was a Toledo weighing scale on which customers could learn their weight free of charge. He shipped in fresh-cut flowers (a real luxury in pre-aviation days). For years, he ran a daily literary advertisement in the Anchorage Daily Times entitled “Loussac’s Daily Gossip,” with the subheading, “Cents and Sense.”

Loussac opened a second drug store, called Z. J. Loussac Drug Store No. 2, on the street level of the Anchorage Hotel Annex on April 28, 1937. The main entrance for the new drug store was located on the corner of Fourth Avenue and E Street. The ultra-modern store featured a spacious interior, unbroken by partitions. Display cases ran the full length of each side and counters for accessories were placed through the center. Lighting played a prominent part in giving an attractive and dignified appearance to the store. There were ultra-modern ceiling lights, ground glass signs with indirect light, and wall cabinets with illuminated lighting. Loussac operated his $35,000 business venture “as a cut price store with the same merchandise plans used by the larger chain stores.”16 Loussac operated the two stores until his retirement in 1943. The original Anchorage Hotel, which stood on the northeast corner of the block, was established in 1916. The corner of Fourth and E Streets was formerly occupied by the Carlquest Jewelry Shop and the Anchorage Power and Light Company.17 In November 1936, the three-story annex opened, with retail space and a banquet room on the first floor.18

World War I had caused problems for Anchorage businesses. According to Loussac: “ . . . it drained the town of the best young men we had. The population shrank. Business disappeared. The town went downhill.”19

Loussac weathered the economic downturn partly by diversifying. In 1920, he became a partner in the Jonesville mine of the Evan Jones Coal Company on 2,240 leased acres on the south slope of Wishbone Hill in the Matanuska Valley. He served as vice-president, president, and treasurer for a number of years. The Evan Jones mine supplied coal to Anchorage and to run the Alaska Railroad.20 Jonesville became the largest producing bituminous coal mine in Alaska. When an underground fire threatened to close the mine in 1922, Loussac and his partners confounded the experts by borrowing a fire engine from Anchorage and, for twelve days, pumped water from a nearby lake into the mine, extinguishing the fire in the coal seams and saving the mine.21

Both the coal and the drug business thrived in Anchorage beginning in 1940, when the town boomed, with military construction, bringing in thousands of troops and hundreds of workers at the beginning of World War II. The military was convinced to buy their coal from the Evan Jones coal mine. Loussac cannily stocked objects that might appeal to soldiers, including souvenirs they could send back to their loved ones. Business boomed, exhausting Loussac who, now approaching sixty years of age, spent his days waiting on customers and his evenings restocking his shelves. It was very difficult to find people to work in his stores; the pay was better on the military base. Now quite wealthy and free of debt, the money was rolling in “by the bushel basket.”22 He was working long hours for money that he did not need. In 1943, Loussac sold both his drug stores.23

Loussac owned Anchorage property, including an apartment building on D Street and the Loussac-Sogn Building at Fifth Avenue and D Street (411 and 425 D Street). Loussac and Dr. Harold Sogn, a respected local physician, were the original owners. Built in 1946-1947, the Loussac-Sogn Building was the largest commercial building in Anchorage and was located on the outskirts of the business district; it still stands.24

Community Service

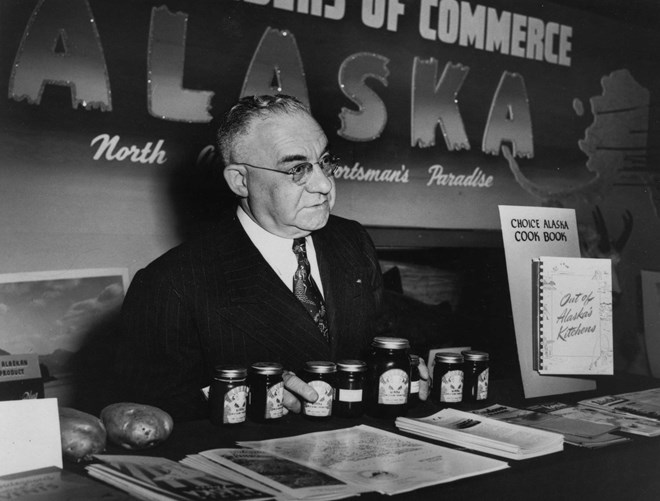

After many successful years running a pharmacy business, Loussac took up community service and became broadly and deeply involved in Anchorage civic activities. At one time or another, he served as president of the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce, Anchorage Times Publishing Company, Pioneer Lodge (Igloo No. 15), Rotary Club, and the Western Alaska Fair Association. He was a member of the Alaska-Yukon Pioneers, B’nai Brith, Elks, Knights Templar, Masons, Shriners, Pioneers of Alaska, Rotary Club, Territorial Board of Pharmacy (Vice-President), and the Zionist Organization of America. He was the founder and first president of the League of Alaskan Cities and a trustee of Alaska Methodist University. During World War II, he served as chairman of the War Bond Loan and National War Fund to direct war bond drives.25 He served on the board of the Alaska Housing Authority at a time when there was not enough housing for all the newcomers arriving in Anchorage. Interestingly, Loussac was not formally naturalized as a United States citizen until October 16, 1945. In addition to becoming a citizen in 1945, Loussac petitioned the U.S. District Court at Anchorage to have his original name, Zachar Luzak, changed to Zachary Joshua Loussac, the form he had been using for years.26 In 1946, he was voted the “outstanding citizen of Alaska” by the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce.

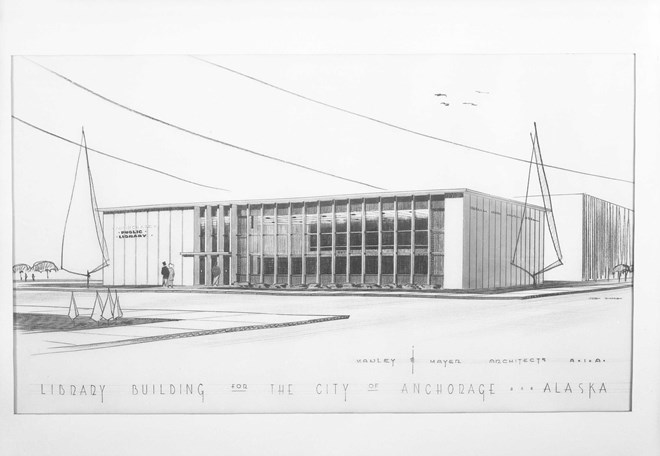

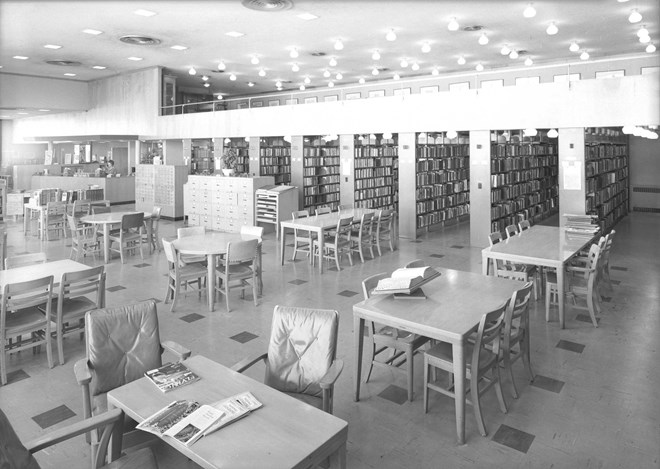

Loussac Foundation

In 1946, Loussac used half his wealth to establish the Loussac Foundation to be used for “social, scientific and cultural activities in the Anchorage area.”27 Loussac said: “The people of Anchorage have been good to me. Everything that I earned came from here and I want it used here."28 One of the major achievements of the Loussac Foundation was the construction of the original Z. J. Loussac Library on the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and F Street, which operated from 1954 to 1985.29 Income through his foundation funded the entire cost of the building.30 In 1986, the new Z. J. Loussac Library opened at 3600 Denali Street in midtown Anchorage as the flagship public library in Anchorage. The Z. J. Loussac Library houses a small but fine collection of Sydney Laurence and Eustace Ziegler paintings that Loussac bequeathed to Anchorage in his will.31 The foundation also contributed funds to the University of Alaska Library, and to establish Alaska (Methodist) Pacific University, Sheldon Jackson College, and the King’s Lake Boys Camp.32 The Loussac Foundation’s funds were later made part of the Rasmuson Foundation.

Mayor of Anchorage (1948-1951)

Loussac was elected mayor of Anchorage for three one-year terms from 1948 to 1951. While Loussac was mayor, federal marshals clamped down on illegal gambling, particularly gambling involving slot machines. He also was instrumental in securing passage of a major general obligation bond for basic city improvements.33

Later Years

In 1949 Loussac, a lifelong bachelor, at the age of sixty-six married the former Mrs. Ada Harper, who ran the Colonial Dress Shop in Anchorage and whose store was located in one of Loussac’s buildings. In 1953, the couple moved to Seattle, where they lived modestly. In 1956 Loussac received an honorary degree from the University of Alaska. The University praised Loussac as a “pioneer Alaskan, philanthropist, and public servant.”

In 1962, city leaders remembered Loussac’s extraordinary generosity. The city council proclaimed his eightieth birthday to be “Z. J. Loussac Day” (July 13, 1962). The Loussacs returned to Anchorage for Z.J.’s eightieth birthday and community celebration. The Anchorage Daily Times published a special, sixteen-page supplement on July 10, 1962, devoted to Loussac’s life and career. Loussac died in Seattle on March 15, 1965 at the age of eighty-two.34 He is buried in Angelus Memorial Park Cemetery in Anchorage. His widow, Ada Nova Loussac, died July 14, 1980, in Seattle, Washington.35

Endnotes

- Stephen Haycox, “Loussac left legacy of fortune, good will to city,” Anchorage Daily Times [ca. spring 1985], in File: Z.J. Loussac, Bagoy Family Pioneer Files (2004.11), Box 5, Atwood Research Center, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage, AK.

- Evangeline Atwood, Anchorage: All-American City (Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort, 1957), 48.

- “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist: The Story of Z.J. Loussac,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 16, 1962, 4.

- Entry for “Zachary Joshua Loussac,” Tewkesbury’s Who’s Who in Alaska and Alaska Business Index (Seattle, WA: Tewkesbury Publishers, 1947), 48; and “Zachary J. Loussac,” in Edmond C. Jeffery, ed., Alaska: Who’s Here, What’s Doing, Who’s Doing It (Anchorage: Jeffery Publishing Company, 1955), 119.

- Evangeline Atwood, “The Loussac Story,” Dedication Program, Z.J. Loussac Public Library, June 1, 1955, Alaska Collection, Z.J. Loussac Library, Anchorage, AK.

- Evangeline Atwood, “The Loussac Story,” 1.

- Matthew, J. Eisenberg, “Zachary J. Loussac,” in “The Last Frontier: Jewish Pioneers in Alaska,” Rabbinic Thesis (Cincinnati, OH: Jewish Institute of Religion, Hebrew Union College, 1991), 95.

- “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 5; and Matthew J. Eisenberg, “The Last Frontier: Jewish Pioneers in Alaska,” 95-96.

- Matthew J. Eisenberg, “The Last Frontier: Jewish Pioneers in Alaska,” 96.

- Loussac recalled that it took twelve years to pay off his Iditarod debts. Evangeline Atwood stated that “the interest rates were so high in those days that it actually meant paying almost twice the amount of the debt.” “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 7; and Evangeline Atwood, “The Loussac Story,” 2.

- “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 7.

- “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 7-8; “Loussac Will Leave Juneau for Anchorage,” Daily Alaska Dispatch (Juneau), August 13, 1916, 4; and R. L. Polk and Company, Polk’s Alaska-Yukon Gazetteer and Business Directory, 1915-16 (Seattle, WA: R. L. Polk & Co., 1916), 321 and 325.

- “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 8.

- Evangeline Atwood, “The Loussac Story,” 3.

- Rae Arno, Anchorage Place Names: The Who and Why of Streets, Parks, and Places (Anchorage: Todd Communications, 2008), 46-47.

- “Loussac to Open New Drug Store next Wednesday,” Anchorage Daily Times, April 24, 1937, 1; and “Alaska’s Most Modern Drug Store Opens Here,” Anchorage Daily Times, April 27, 1937, 5.

- “Excavation for Hotel Addition to be Sluiced,” Anchorage Daily Times, June 6, 1936, 8.

- “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 9; Matthew J. Eisenberg, “The Last Frontier: Jewish Pioneers in Alaska,” 98-99; Preston Jones, City for Empire: An Anchorage History, 1914-1941 (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2010), 66 and 147-148; and National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, “Loussac-Sogn Building,” AHRS Site No. ANC-359, April 14, 1998, National Register of Historic Places, http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NRHP/Text/98000567.pdf (accessed June 24, 2015).

- “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 8.

- Charles C. Hawley, “Evan William Jones (1880-1950),” Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation (Anchorage: 1999), http://alaskamininghalloffame.org/inductees/jones.php (accessed June 24, 2015). The other partners were Oscar Anderson, Jack Collins (a hotel man), Evan Jones, Dr. Blyth (a dentist), and Dr. Boyle, an M.D. Evan Jones served as general manager.

- “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 8; Report of the Governor of Alaska to the Secretary of the Interior (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921): 34; Stephen Haycox, A Warm Past: Travels in Alaska History: 50 Essays (Anchorage: Press North, Inc., 1988),39; and Ed Ferrell, compiler and editor, Biographies of Alaska-Yukon Pioneers, Volume 3 (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 1997), 202-203.

- “City Sets Loussac Day to Honor Philanthropist,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 12.

- “Z. J. Loussac Ends Long Drug Career July 1,” Anchorage Daily Times, June 28, 1943, 1.

- National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, “Loussac-Sogn Building,” AHRS Site No. ANC-359, April 14, 1998, National Register of Historic Places; and Alison K. Hoagland, Buildings of Alaska (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 88-89.

- Matthew J. Eisenberg, “The Last Frontier: Jewish Pioneers in Alaska,” 99-100; Tim Moffatt, “Zachary J. Loussac,” Alaska Business Monthly, January 1989, 29; and Tewkesbury’s Who’s Who in Alaska and Alaska Business Index (Seattle, WA: Tewkesbury Publishers, 1947), 48.

- Index card for Zachary Joshua Loussac [Zachar Luzak], National Archives Microfilm Publication M1788, Indexes to Naturalization Records of the U.S. District Court for the District, Territory, and State of Alaska (Third Division), 1903-1991, Roll 11, U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project) [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed June 26, 2015).

- Matthew J. Eisenberg, “The Last Frontier: Jewish Pioneers in Alaska,” 100.

- Preston Jones, City for Empire: An Anchorage History, 1914-1941, 66.

- The original Z. J. Loussac Library was demolished in 1981 to make way for the William A. Egan Civic and Convention Center. “Zachary Joshua Loussac, Jewish Pharmacist, Philanthropist, & Mayor of Anchorage, Alaska,” Jewish Museum of the American West, Western States Jewish Historical Association, http://www.jmaw.org/loussac-jewish-mayor-anchorage-alaska (accessed June 24, 2015).

- File: Loussac, Zachary J., Minutes of a Special Emergency Meeting, Anchorage City Council, August 14, 1953, p. 38, Bernice Bloomfield Collection of Jews in Alaska (B1986.1.1), Box 2, File Folder 23, Atwood Research Center, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage, AK.

- “A New Loussac Gift,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 18, 1980, A-6; and Cynthia Elek, The Loussac Collection: Paintings of Sydney Laurence and Eustace Ziegler, Alaska Collection, Z. J. Loussac Public Library, Anchorage, Alaska (Anchorage: Municipality of Anchorage, 1986).

- Stephen Haycox, A Warm Past: Travels in Alaska History: 50 Essays, 40.

- Evangeline Atwood, Anchorage, All-American City, 112; Evangeline Atwood, “The Loussac Story,” 3; and Stephen Haycox, A Warm Past: Travels in Alaska History, 40.

- “Former Mayor Z. J. Loussac Dies in Seattle At 82,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 16, 1965, 1.

- “Ada Nova Loussac,” in “End of the Trail,” Alaska-Yukon Magazine, October 1980, 72.

Sources

By Walter Van Horn and Bruce Parham, June 25, 2015. This essay substantially revised and updated the entry that originally appeared in John P. Bagoy, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 128-129. See also the Z.J. Loussac file, Bagoy Family Pioneer Files, Box 5, Atwood Resource Center, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage, AK.

Preferred citation: Walter Van Horn and Bruce Parham, “Loussac, Z.J. ‘Zach’,” Cook Inlet Historical Society, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, http://www.alaskahistory.org.

Major support for Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, provided by: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Atwood Foundation, Cook Inlet Historical Society, and the Rasmuson Foundation. This educational resource is provided by the Cook Inlet Historical Society, a 501 (c) (3) tax-exempt association. Contact us at the Cook Inlet Historical Society, by mail at Cook Inlet Historical Society, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, 625 C Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 or through the Cook Inlet Historical Society website, www.cookinlethistory.org.