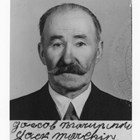

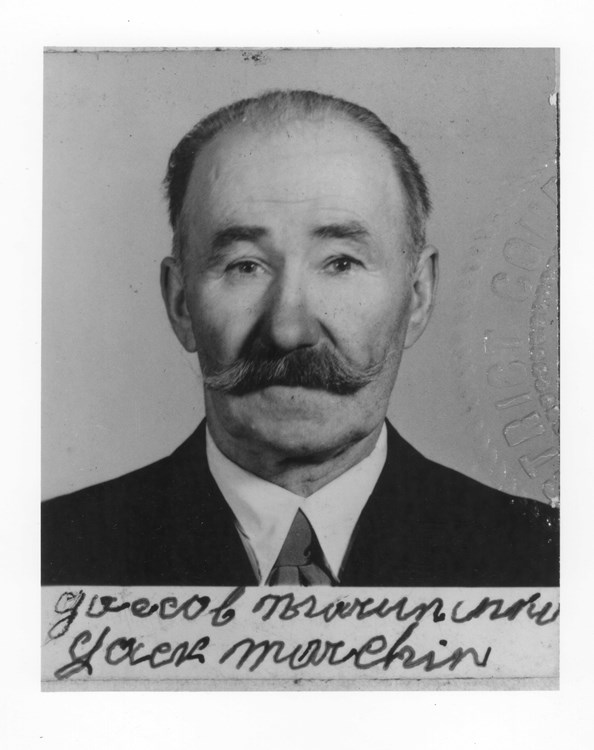

Marunenko, Jacob "Russian Jack"

1883-1971 | Local Character

Jacob Marunenko (also known as “Russian Jack,” "Jack Marchin," "John Marchin," "M. Marchin," and "Jake Merchen") was an immigrant who became one of Anchorage’s more colorful and legendary characters. While living in Anchorage, Marunenko sometimes shortened his name to Jack Marchin. “Russian Jack” was his well-known nickname. He was a bootlegger, moonshine maker, and criminal. On January 12, 1938, Jacob Marunenko’s nickname became even better known when he was charged with murder after shooting the owner of a taxicab company, Milton Hamilton, and killing him.1 He was convicted of manslaughter and received a two-and-a-half year sentence in the federal penitentiary at McNeil Island, Washington. Over the course of two decades, his nickname became “attached to a street, a large city park, an animal hospital, a bank branch, an apartment complex, a post office, and even an elementary school.”2

Russia to America

Jacob Marunenko was born on October 23, 1883 in the village of Parievka (or Pariivka), located in Ukraine, southwest of Kiev. He married in Parievka in 1907 and he and his wife Melania had two children: Stepanka, born in 1909, and Roman, born in 1912.3 The family lived together for only a short time, as something caused him to leave and never return.

Immigrants from the Imperial Russian Empire who settled in Canada and the United States included Russians, Jews, Ukrainians, and Finns. Many of these immigrants began arriving in large numbers during the period from 1880 to 1914, but especially after 1905. The majority were impoverished peasants who left in the fading days of czarist Russia to seek freedom, economic prosperity, and escape anti-Jewish pogroms before the outbreak of World War I brought a sudden end to the movement of people.

Marunenko immigrated to the United States in either 1912 or 1915, depending on which records are to be believed. One source, the April 1915 ships’ passenger arrival list, indicates that he first arrived in Canada, landing at Halifax in April 1912. Using the alias, "John Marchin," he listed his last permanent residence as Princeton, British Columbia, and occupation as a laborer. In April 1915, he entered the United States through the port of entry at Oroville, Washington, in north-central Washington, and indicated that he was directly proceeding to Skagway.4 Marunenko’s 1951 declaration of intention for naturalization indicates that he first traveled on a Canadian Pacific Railway train south from Canada to Blaine, Washington in May 1915.5 The 1920 U.S. Census says that he came to the United States in 1912, the same year his son was born.6

It was common for the head of the family to come first, to save, and to send for the family later. In his naturalization records and other official documents, Marunenko never denied having a family. Once in the United States, there is no indication that he ever returned to Ukraine or that his family ever joined him. According to family sources, shortly after he settled in Alaska, he contacted his wife, Melania, and their two children. Due to the family's impoverished circumstances in the village of Parievka, she was unable to leave. The family never talked openly about him, because if anyone said they had a relative in the United States, the entire family could suffer prosecution by local authorities--they might even be killed.7

Arrival and Early Life in Anchorage

Marunenko claimed to have arrived in Anchorage in 1915. He came to work on the construction of the Alaska Railroad, and after its completion, remained doing odd jobs and lived in cabins or shacks on the social and economic periphery of the community. Marunenko first surfaced in 1916, when he worked as a laborer for the Alaskan Engineering Commission (AEC), which was then building the Alaska Railroad.8 His World War I draft card, dated October 24, 1918, states that he was a laborer employed by the AEC, and that his wife lived in Kiev.9 In the 1920 U.S. Census, the census enumerator lists him with a new name, "Jack Marchin," the name that he is known by for the rest of his life. He could read and write, and owned a cabin, but had not obtained U.S. citizenship. He was the proprietor of the Montana Pool Room, located at 435 Fourth Avenue.10 Marunenko either lost or disposed of the Pool Room because he could not obtain legal title as a non-U.S. citizen. This was also his residence until at least 1922.11 Pool halls in Anchorage tended to be centers for illegal gambling, indicating that he had knowledge of the illegal side of Anchorage life.12

Bootlegging or Illegal Traffic in Liquor

Prohibition offered another avenue for illegal activity. The sale and manufacture of liquor had been prohibited in Anchorage since 1915 and it was expanded by a territorial prohibition law in 1916. There was a nationwide constitutional ban on the sale, production, importation, and transportation of alcoholic beverages that remained in effect from 1920 to 1933.

Although Anchorage was legally dry until 1933, the consumption of alcohol far exceeded the national average. When workers in Alaska’s basic industries came to town after spending long periods of time in remote areas, they tried to make up for lost time. Bootlegging was a big business as illegal moonshine was the only liquor available.13 Men like Jacob "Russian Jack" Marunenko were relied upon to make deliveries in plain sight. As a boy, the late John Bagoy witnessed “Russian Jack” distributing liquor: “He’d get a woman to push a baby buggy with a doll and a jug of moon underneath it.”14 Marunenko reportedly made his own “squirrel juice” from an illicit moonshine still located on a large parcel of land that became one of Anchorage’s largest parks, Russian Jack Springs Park.

As “Squatter” at Russian Jack Springs

It appears that Marunenko was a “squatter” on his so-called Russian Jack Springs “homestead.” This 320-acre tract of rolling, well-treed land with a large spring was located roughly three miles east of downtown Anchorage. In the 1920s, he built a cabin on this tract. His nickname, “Russian Jack,” became associated with the land. General Land Office records indicate that Marunenko only had a permit to harvest timber.15 Marunenko was an alien and not a U.S. citizen. He could not legally have obtained a patent or deed of title until a declaration of intention to become a U.S. citizen was filed in the U.S. District Court.

The homestead was actually in the names his best friend, Peter Toloff (also a Russian immigrant) and a Nicholas Darlopaulos (or Nicolaos Devlopoulos). They were friends of Marunenko and appear to have allowed him to live on their land. Toloff filed for a 160-acre homestead on the western half part of the land, lying to the north and south of today’s DeBarr Road. Nicholas Darlopaulos filed on a 160-acre tract in the eastern half. Under the Homestead Act of 1862 (12 Stat. 392), as homesteaders both Toloff and Darlopaulos would be given a patent or legal title to the land if they fulfilled certain conditions. In general, they had to build a home on the land, live there for five years, make improvements to the land, and give proof of citizenship.16 Neither “proved up” and, therefore, never received title to the land from the federal government.

Although Marunenko never received legal title to the land, he set up a moonshine still and brought his product into town and made deliveries, “like a milkman working his route.”17 He had regular customers including both local prostitutes and “some of the town’s more prominent citizens.”18 During the summer, the business was run from the cabin at Russian Jack Springs and, during the winter, out of a house on 5th Avenue, between A and Barrow Streets. Although the business was carried on outside of the law for many years, he largely avoided trouble.

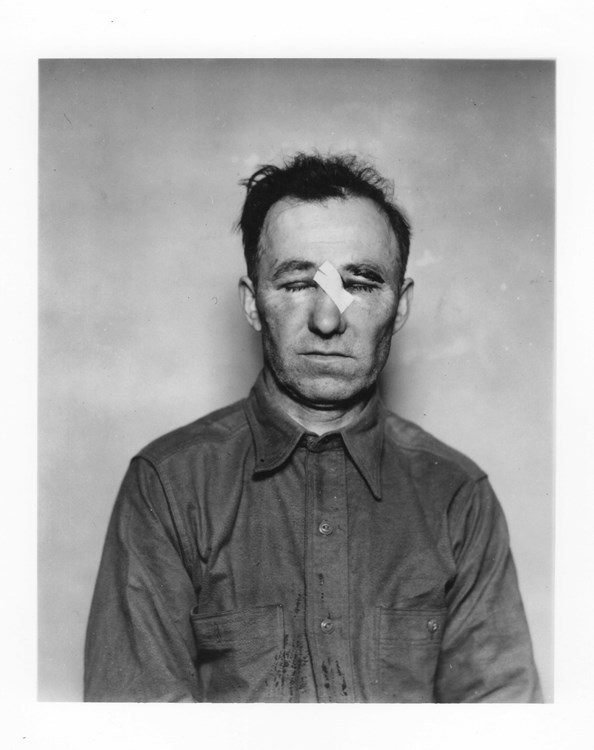

“Russian Jack” Murder Trial (1937)

In 1933, prohibition ended and this required Marunenko to change his occupation. He worked as a carpenter and wood cutter, and did hauling with his wagon.19 Apparently he moved from his cabin closer to town, living on Second Avenue in what would be the eastern end of Anchorage. During this time he became friends with Mrs. Doris Simmons and her brothers, Raymond and Stanley Mahle, who lived on a nearby street. On Sunday, March 21, 1937, he was invited to the Simmons house for the evening. The early evening was spent convivially drinking wine. The atmosphere changed when Milton Hamilton, a thirty-one year-old taxi operator with a reputation for being rough, arrived with a case of beer around midnight. While the exact cause and order of events are now murky, there is no question that Hamilton beat Marunenko severely about the face and head, causing extensive bleeding, breaking of two teeth and possibly causing a fractured skull. The quarrel was over Mrs. Simmons. Marunenko left the premises but, according to his own testimony, returned to the Simmons house after midnight to pick up his coat before going home. According to Marunenko, someone grabbed him from behind while he was in the kitchen and began choking him. Afraid for his life, he found a gun that he carried in his coat pocket and blindly fired a shot, which killed Hamilton. Report of the killing was front page news in the Anchorage Daily Times the next day, March 22nd.20 That morning, he was taken to the federal jail. After a preliminary hearing, he was bound over without bail until the murder trial occurred ten months later.

From January 10-17, 1938, Marunenko was tried before the U.S. District Court at Anchorage for the murder of Milton Hamilton. There was a jury of eleven men and one woman, all of whose names appeared in the Anchorage Daily Times. He was represented by Clyde Ellis, who had just been elected president of the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce. Perhaps the most dramatic testimony was given by Marunenko himself, arguing that he acted in self-defense. The trial generated a great deal of interest as there were about one hundred spectators in the court room. At the end of the third day, the jury withdrew and deliberated all night. They found Marunenko guilty of manslaughter, but urged the judge to be lenient. Judge Simon Hellenthal could have given him a sentence of anywhere from one to twenty years in prison. Judge Hellenthal sentenced him to two and a half years in the federal penitentiary at McNeil Island, Washington, near Seattle.

Later Years

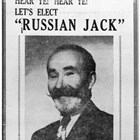

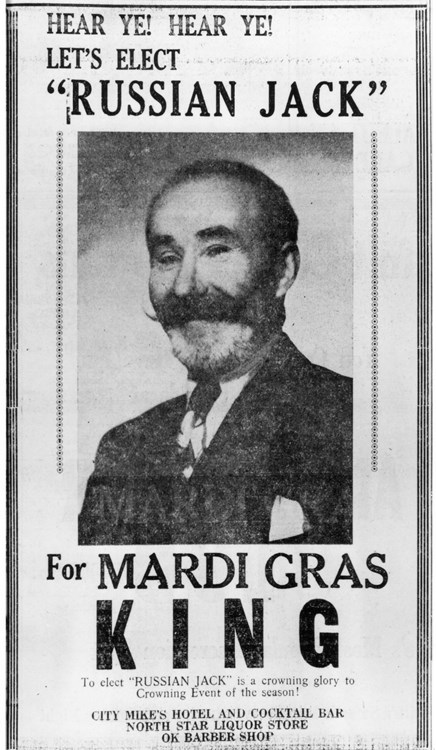

After serving his sentence, Marunenko returned to Anchorage. During the February 1948 Fur Rendezvous, several businesses (City Mike’s Hotel and Cocktail Bar, North Star Liquour Store and the OK Barber Shop) sponsored an advertisement in the Anchorage Daily Times encouraging people to vote for “Russian Jack” Marchin as “Mardi Gras King.”21 Although Marunenko did not win (he came in last place), he was proclaimed a prince. He finally became a U.S. citizen in 1954, at the age of seventy.22 He probably moved around quite frequently during his last twenty years in Anchorage. It is known that between 1956 and 1958 he again lived at Peter Toloff’s house at 105 East Second Avenue.23

Sometime after 1959, Marunenko moved to California. By 1967 he was in Arvin, a small community in a desolate desert area some fifty miles east of Bakersfield. He died there as Jack Marchin on October 28, 1971 of heart disease at the age of eighty-eight and was placed in an unmarked grave.24 Later, John Bagoy visited his gravesite and placed a grave marker.

Russian Jack Springs Park

The colorful history of the Russian Jack Springs Park (an “island of forest in the midst of Anchorage’s largest city”25) is more than just someone with an interesting, catchy nickname. After the United States entered World War II, the U.S. Army expanded Fort Richardson for wartime security. Several large tracts of land in east Anchorage were needed for this expansion. Having no choice but to give up their land, the large tracts of Toloff and Darlopaulos, including Marunenko’s former home, were “acquired” by the U.S. military in 1943 for $4,800 in compensation. Five years later, the land was declared surplus property and sold by the U.S. War Assets Administration to the City of Anchorage for $16,000. The City of Anchorage expressed interest in the two parcels for use as a city park and the fresh water of “Russian Jack Springs” was reserved as a secondary water supply source.26

In 1951, the Anchorage Police Department established a city prison farm on the Russian Jack Springs site. Located at the northwest corner of DeBarr Avenue and Boniface Parkway, the prison farm held low-security inmates on what is now the Russian Jack Springs Park greenhouse and public golf course.27 The city prison honor farm was a complete truck farm operation; it supplied all the vegetables for the city jail, the prisoners themselves, and several agencies.28 The food raised, processed, and preserved at the farm played a large part in keeping “board” bills for city jail inmates at $0.18 per meal.29 In 1968, the prison farm was moved to a 160-acre site near the former Point Campbell Military Reservation and the Anchorage International Airport runways so that Russian Jack Springs could be developed as a recreation area. In 1972, the Anchorage Social Development Center temporarily moved into the former city honor farm at Russian Jack Springs to provide rehabilitation and recovery services for alcoholics. A few years later, the Center was relocated to a new site near the Anchorage International Airport.30

Dubious Legacy

Beginning in the late 1960s and into the 1970s the tract was developed as a park and named Russian Jack Springs Park. The neighboring area became known as Russian Jack, with an elementary school, a community council, and a branch of the National Bank of Alaska also adopting the name Russian Jack--conveying respectability to the name that many of Jacob Marunenko’s fellow citizens of earlier years would not have accorded him.

Endnotes

- “‘Russian Jack’ Marchin Tells his Story,” Anchorage Daily Times, January 12, 1938, 1 and 4.

- Bruce Merrell, “Russian Jack: Anchorage Pioneer and Criminal,” in Politics and Government in Alaska’s Past: Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Alaska Historical Society, Juneau, Alaska, October 4-7, 1995 (Anchorage: Alaska Historical Society, 1995), 95.

- Index card for Jack Marchin, a/k/a/ Jacob Marunenko, National Archives Microfilm Publication M1788, Indexes to Naturalization Records of the United States District Court for the District, Territory, and State of Alaska (Third Division), 1903-1991, Roll 12, U.S., Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project) [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed February 16, 2015). The Declaration of Intention of March 27, 1951, petition for Naturalization of March 5, 1953, and index card indicate that the village of "Parevka" [Parievka] was in the Ukraine. It appears that federal officials misspelled the name of the village, as it is spelled as "Parevka," missing the letter i. See also, Laurel Downing Bill, "History comes Full Circle for Aunt Phil,"September 13, 2018, Aunt Phil's Trunk https://auntphilstrunk.com/history-comes-full-circle-for-a (accessed January 6, 2019); Dave Goldman, "Alaska History Comes Full Circle for a Family from California," September 13, 2018, KTVA-TV (Channel 11), Anchorage, AK, https://www.kvta.com/story/39089403/alaskan-history-com (accessed January 6, 2019); and Tanya Marunenko Malinovskiy, January 6, 2019, Interview by Bruce Merrell, e-mail message to Bruce Merrell.

- John Marchin, “List or Manifest of Alien Passengers Applying for Admission to the United States from Foreign Contiguous Territory, Port of Oroville, Washington, line 6, sheet no. 2, page 307, April 1915, Manifests of Passengers Arriving at St. Albans, VT, District through Canadian Pacific and Atlantic Ports, 1895-1954, Border Crossings: From Canada to U.S., 1895-1956 [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed February 14, 2015).

- According to the Certificate of Arrival for Jacob Marunenko, issued February 20, 1933, he arrived on May 7, 1915 at the port of entry of Blaine, Washington. See, Jacob Marunenko a/k/a Jack Marchin, Declaration of Intention, A-1290, March 27, 1951, in Naturalization Petition File No. A-1736, File: A1725-A1752, Petitions for Naturalization, 1916-1960, Box 9 (U.S. District Court, District of Alaska, Third Division, Anchorage), Records of the District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21, National Archives at Anchorage, Anchorage, AK (transferred to the National Archives at Seattle, Seattle, WA, in 2014). See also, Bruce Merrell, “Russian Jack: Anchorage Pioneer and Criminal,” Politics and Government in Alaska's Past: Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Alaska Historical Society, Juneau, Alaska, October 4-7, 1995), 95.

- Jake Merchen [Jacob Marunenko], Anchorage, Third Judicial District, Alaska, ED 11, stamped page 41, National Archives Microfilm Publication T625, Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1920, Roll 2031, 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed February 15, 2015).

- Bruce Merrell, “Russian Jack: Anchorage Pioneer and Criminal,” Politics and Government in Alaska's Past: Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Alaska Historical Society, Juneau, Alaska, October 4-7, 1995, 95-96; and Laurel Downing Bill, "History comes Full Circle for Aunt Phil,"September 13, 2018, Aunt Phil's Trunk https://auntphilstrunk.com/history-comes-full-circle-for-a (accessed January 6, 2019).

- See entry for “M. Marchin,” in “Undelivered Checks,” for employees of the Alaskan Engineering Commission, in the Alaska Railroad Record, v. 1, no. 5, December 12, 1916, 34. See also Jacob Marunenko, World War I Draft Registration Card, Local Board No. 10, Anchorage, Third Judicial District, Alaska, October 24, 1918, National Archives Microfilm Publication M1509, World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Roll AK1, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1918-1918 [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed February 16, 2015).

- Jacob Marunenko, World War I Draft Registration Card, October 24, 1918; U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed February 16, 2015).

- Jacob Marunenko, 1920 U.S. Census, Anchorage, Third Judicial District, Alaska, 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed February 15, 2015).

- John Bagoy, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 130; and Rae Arno, Anchorage Place Names: The Who and Why of Streets, Parks, and Places (Anchorage: Todd Communications, 2008), 64-65.

- William H. Wilson, “The Urban Frontier in the North,” in Interpreting Alaska’s History: An Anthology, ed. Mary Childers Mangusso and Stephen W. Haycox (Anchorage: Alaska Pacific University Press, 1989), 253-257.

- Evangeline Atwood, Anchorage: Star of the North (Tulsa, OK: Continental Heritage Press, Inc., 1982), 63-64.

- Scott Christiansen, “You don’t know Russian Jack,” Anchorage Press, v. 9, ed. 9, March 2-8, 2000, 10.

- Liz Wilson, compiler, A Brief History of Russian Jack Springs Park (Anchorage: Parks and Recreation Division, Department of Cultural and Recreational Services, Municipality of Anchorage, 1996); and Bruce Merrell, “Russian Jack: Anchorage Pioneer and Criminal,” Politics and Government in Alaska's Past: Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Alaska Historical Society, Juneau, Alaska, October 4-7, 1995, 102.

- Anne Bruner Eales and Robert M. Kvasnicka, editors, Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives, Third Edition (Washington, DC: National Archives Trust Fund Board for the National Archives and Records Administration, 2000), 293.

- Bruce Merrell, “Russian Jack: Anchorage Pioneer and Criminal,” Politics and Government in Alaska's Past: Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Alaska Historical Society, Juneau, Alaska, October 4-7, 1995, 98.

- Ibid.

- “Russian Jack: A Colorful Man who liked his Isolated Life,” Anchorage Times, August 19, 1979, C-2; and “Anchorage Man Dead after Quarrel; Jury Names ‘Russian Jack’ Marchin,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 22, 1937, 1 and 8.

- “Anchorage Man Dead After Quarrel; Jury Names ‘Russian Jack’ Marchin,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 22, 1937, 1 and 8. See also, Bruce Merrell, “Russian Jack: Anchorage Pioneer and Criminal,” Politics and Government in Alaska's Past: Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Alaska Historical Society, Juneau, Alaska, October 4-7, 1995, 99.

- Bruce Merrell, “Russian Jack: Anchorage Pioneer and Criminal,” Politics and Government in Alaska's Past: Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Alaska Historical Society, Juneau, Alaska, October 4-7, 1995, 101-102.

- Naturalization case file for Jacob Marunenko [AKA] Jack Marchin, No. A-1736, Petitions for Naturalization, 1916-1960; and “35 Take Oath as New American Citizens,” Anchorage Daily Times, February 22, 1954, 7.

- The house no longer stands as this area was cleared of all buildings after the 1964 Alaska Earthquake. Bruce Merrell, “Russian Jack: Anchorage Pioneer and Criminal,” Politics and Government in Alaska's Past: Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Alaska Historical Society, Juneau, Alaska, October 4-7, 1995, 103.

- Jack Marchin, Certificate of Death, Office of Vital Records and Statistics, California Department of Health Services, October 28, 1971; and “Graveside Rite for Miss Espinoza,” Arvin (California) Tiller, November 3, 1971, 6.

- Liz Wilson, compiler, A Brief History of Russian Jack Springs Park.

- Ibid.

- Fritz Pumphrey, “City Prison Farm has Remarkable Record of Progress, Advancement," Anchorage Daily Times, January 25, 1956; 9; Bob Miller, “City’s Prison Farm Paying Off in Several Ways,” Anchorage Daily News, September 21, 1960, 4; “Voters to Decide on Prison Bond,” Anchorage Daily Times, September 28, 1966, 2; and Rae Arno, Anchorage Place Names: The Who and Why of Streets, Parks and Places, 65.

- “City Prisoners Farm 30 Acres,” Anchorage Daily News, June 14, 1961, 3.

- Department of the Month,” City of Anchorage Municipal Bulletin, September 1960; “Farm Products Keep Meal Costs Down,” City of Anchorage Municipal Bulletin, October 1963, 3; and “Zoo Possibilities Being Explored,” City of Anchorage Municipal Bulletin, February 1966, 1.

- Dave Webster, “Modern Prison Farm Opens,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 13, 1968, 1; Rosemary Shinohara, “No Lock at New Alcohol Care Center,” Anchorage Daily Times, October 17, 1972, 13; and “Local Alcoholic Center could become Standard,” Anchorage Daily Times, September 22, 1973, 22.

Sources

This entry for Jacob Marunenko originally appeared in John P. Bagoy, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 130. Much of the information in this essay is based on previous biographical research by Bruce Merrell, who also provided access to his research files on Marunenko. See, File: Marunenko, Jacob "Russian Jack," Cook Inlet Historical Society, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, Project Research Files, ca. 1919-2016 (B2017.004), Box 8, Atwood Resource Center, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage, AK. Note: edited, revised, and expanded by Bruce Parham and Walter Van Horn, March 7, 2014, August 6, 2017, and January 22, 2018. Updated May 7, 2019.

Preferred citation: Bruce Parham and Walter Van Horn, “Marunenko, Jacob ‘Russian Jack’,” Cook Inlet Historical Society, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, http://www.alaskahistory.org.

Major support for Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, provided by: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Atwood Foundation, Cook Inlet Historical Society, and the Rasmuson Foundation. This educational resource is provided by the Cook Inlet Historical Society, a 501 (c) (3) tax-exempt association. Contact us at the Cook Inlet Historical Society, by mail at Cook Inlet Historical Society, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, 625 C Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 or through the Cook Inlet Historical Society website, www.cookinlethistory.org.